Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Today: Allan Dyen-Shapiro is a Ph.D. biochemist whose non-linear career has taken him through the worlds of science and education and left him with many stories to tell. He finished his first novel and is looking for an agent/publisher. Short stories in addition to those in anthologies/journal issues available on Amazon can be read or are linked from his website: allandyenshapiro.com.

You can also access his blog from the website, which focuses on issues of relevance to those who would like his fiction: science, environmentalism, futurism, writing, and science fiction. He writes mostly near-future SF but has dabbled in alternate history, humor, cli-fi, and cyberpunk.

Friend or follow him on Facebook at allandyenshapiro.author, on Mastodon @Allan_author_SF@wandering.shop, and on Twitter @Allan_author_SF.

Authors who have influenced him the most include Neal Stephenson, Paolo Bacigalupi, William Gibson, Harlan Ellison, Thomas Pynchon, John Brunner, and Kim Stanley Robinson.

Thanks so much, Allan, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: When did you know you wanted to write, and when did you discover that you were good at it?

Allan Dyen-Shapiro: I decided I wanted to write fiction when I left the science world with ideas that I wanted to have starting conversations and no other way to get them out into the world. Discovering that I’m good is an ongoing process: my first published story that I got paid money for; my first story to sell for pro rates; my stories that qualified me for membership in SFWA and Codex; my continuing to make sales (including some at pro-rates); my getting a just-under-novella-length work out as a book with a small press. External validation was critical to convincing me that I wasn’t just playing at being an author. Of course, I’m hoping for more such things to happen (selling my novel to a traditional publisher, cracking the tip-top short fiction markets, winning a literary award), but I’ve had enough success to keep my going regardless of whether I ever achieve these milestones.

JSC: Have you ever taken a trip to research a story? Tell me about it.

ADS: Sort of. I had a story that eventually sold for pro rates spring from a trip. My vacation in South Dakota led directly to an alternate history story where the point of divergence was that Crazy Horse was never murdered. It’s set in a fictional, present-day Lakota Democratic Republic where the chief adversaries are climate change and domination by the Peoples Republic of China. If you’re into history, South Dakota is an awesome place to visit.

JSC: Are there underrepresented groups or ideas featured in your book? If so, discuss them.

ADS: Absolutely. It’s set in Oakland after a major ecological disaster that dropped the rents and housing prices and allowed the type of people who always lived there before the tech bros gentrified it to move back. Oakland had been majority black since the 1940s, so many of the characters, including two of the most important ones, are black. One of the most important characters is a lesbian; still another is a gay man. It wouldn’t be Oakland without diversity!

As for underrepresented ideas, that technological progress and community organizing might both be necessary to solve an environmental problem seems obvious to me, but I haven’t seen it a lot. Usually, the focus is on one or the other.

How to be an ally to a disadvantaged community, how to leverage expertise without being a white savior—yeah, I haven’t seen much of that either, but with Trump busy destroying the careers of American scientists, the ones who don’t escape to another country (surveys show 80% are considering it seriously), might bring more such struggles into everyday life. Depiction in fiction will likely follow.

JSC: Do your books spring to life from a character first or an idea?

ADS: Usually, a character and an idea come about near-simultaneously. If it’s an idea that emerges first, my next step is defining what sort of character would embody the idea. If it’s a character, my next step is figuring out why I want to write about them.

JSC: What book is currently on your bedside table?

ADS: 120 Murders: Dark Fiction Inspired by the Alternative Era. Nick Mamatas is a terrific anthologist, and the 90s had wonderful music. Now that my writing has branched out from science fiction into horror, as the present day and near future of the real world more-and-more resemble a horror story, I have also been reading more horror. I saw this one on sale at Worldcon and snapped it up. I’ve enjoyed many of the stories I’ve read thus far.

JSC: How did you choose the topic for The Day We Said Goodbye to the Birds?

ADS: It started with some real-life experiences that I felt strongly about and a need to put these feelings into writing. And moving away from the Bay Area, I knew I also wanted to pen a love letter to my former home. My home before the tech bros came in and ruined it, that is, but I was long gone by then.

JSC: What inspired you to write this particular story? What were the challenges in bringing it to life?

ADS: The two vignettes from my own life inspired it. In one, the day before I moved away from the Bay Area, I took my baby daughter to her favorite place in the world—Lake Merritt Estuary in Oakland—for one last time. In the second, I witnessed events that led to what the press, in a clear act of racism, called a riot at the 1995 Oakland festival. But these weren’t speculative fiction stories. They would have been literary fiction. And who was going to buy literary fiction from me? So, I wrote a near-future science fiction story to tie them together. Once I’d finished, I learned from critique that the ending didn’t work, and I wasn’t a good enough writer at the time to figure out how to make it work. The draft sat for six years until I became good enough to put the vision I had onto paper.

JSC: What were your goals and intentions in this book, and how well do you feel you achieved them?

ADS: The original goal was to portray the struggles of a scientist whose career had collapsed to do something worthwhile that helped a community he had unintentionally harmed. From the get-go, it had what I wanted to say about environmental racism and scientists’ social responsibility, but the theme of how to be an ally to a community rather than a “white savior” developed over time through many drafts and many rounds of critique. I think I ended up with something unique. I don’t know of anything else like it.

JSC: Let’s talk to your characters for a minute – Are you happy with where your writer left you at the end? (don’t give us any spoilers).

ADS: Well, we wouldn’t have been if he’d stopped the story at the point where the guy thought it might be sellable to the major pro-rate markets for novelettes. It wasn’t—what a foolish optimist this guy was! Only the cool kids and the already successful get to do that. When the editor who’d been considering it for his semipro magazine loved it enough to suggest publishing it in book form and allowed the writer to pen an epilogue, then we became happy with it. The protagonist was the only one with a path forward in the original version. And even his plans were hazy. As it is, several more of us get a happy, hopeful ending.

JSC: What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next? Tell us about it!

ADS: What I’m working on right now is taking the short stories I have that are far enough into the pipeline that they were finished and received at least one round of critique and bringing them to the point of submission to a market. I want to do this before I embark on anything new that is long form.

I have two original short stories that will likely be my next to be published. “Become the New You” is a creepy, anti-capitalist horror story coming out in an anthology from Whisper House Press called Dread Mondays. It drops October 25. There’s something odd about the people working at the Nordstroms where Chloe takes a part-time job to help put food on the table. In “Power and Control through Vocabulary,” a sociopath goes to work for a company that is developing technology to implant thoughts in peoples’ heads. This one will come out in a 2026 issue of Stupefying Stories.

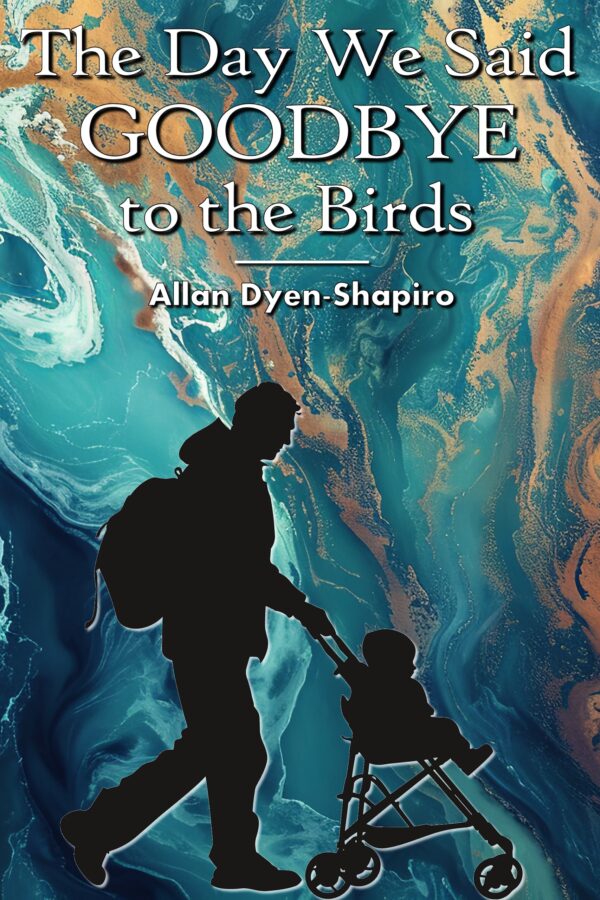

And now for Allan’s new book: The Day We Said Goodbye to the Birds:

“Genocide Joe” is a marked man.

Once a respected microbiologist, now the scapegoat for a GMO-caused ecological disaster that’s turned San Francisco Bay toxic and poisoned thousands, Joe has lost everything: his career, his reputation, his wife, his home, and most of his friends.

To start over where no one knows his face, all he needs to do is catch the bus out of town. But an unexpected transit outage has dumped him in Oakland, so now he must get to the next station on foot, while pushing a baby stroller.

And hoping to pass unrecognized through a city where everyone hates him, and a lot of people want to kill him.

Themes include environmental racism, scientists’ social responsibility, and how to be an ally.

Publisher | Universal Buy Link

Excerpt

Joe’s eighteen-month-old daughter’s hands clutched the seatback as she bounced up and down, blithely unaware of the reason for their escape from the San Francisco Bay Area. Unable to keep pace with the movement, her tie-dyed dress fluttered like a butterfly’s wings. “Train,” she said.

“Yes, Daphne. Train.” Joe positioned his hand on her delicate shoulder. “We’ll be in San Francisco soon.”

She spun around and smiled at him. “Daphne Duck.”

“Daphne Duck.”

When she giggled, he kissed her forehead. Before her birth, when his wife had mentioned the name Daphne to his mother, Mom had worried the nickname, a feminization of Daffy, would emerge and scar Daphne for life. So far, no visible scarring.

On Daphne, at least. It was now ex-wife. Joe had scars.

“Blue line,” the BART train announcer’s voice intoned. The blue line would take them to the Transbay Transit Center in San Francisco, where they’d catch the bus for Oregon.

“Now departing Castro Valley.”

The Oakland Hills fenced off this suburban haven, protecting it from poisonous breezes from San Francisco Bay. Joe couldn’t have afforded the mortgage payments there on the salary paid by his job as a scientist for CyanoCorp, without his wife’s earnings as a corporate lawyer.

Ex-wife. Ex-job.

At the next station, the train shuddered to a stop. “Bay Fair. Please put on protective gear. Position your mask first, then help any small children. Because of high toxin levels in the air today, at all aboveground stations, the doors will not open until compliance has been verified.”

After molding the oblong, gray polyethylene over his nose and mouth, Joe adjusted the clear-plastic window of the eyepiece and fastened the Velcro straps.

“Daddy, funny.”

With fingers spread into imaginary claws, he extended his arms toward her. “Aarrghh! Evil monster on the loose.” He exaggerated the vocal distortion from the mask, hoping Daphne would find it goofy rather than disconcerting.

It worked—Daphne beamed and tittered.

Joe fished her mask from the container and encased her in less than three seconds. His proficiency stemmed from having consulted on testing the manufacturer’s 2031 line of protective gear. He’d previously designed the anti-toxin-derivatized air filter the company had licensed for the masks, his last project before CyanoCorp had canned him in 2030.

In those days, he’d risen each morning entasked with a life mission—the world, his to save. These days, not so much.

“Thank you for wearing your anti-toxin mask. The doors will now open.”

Many departing passengers wheeled suitcases; destination SFO, they’d escape via airplane. Armani suits pushed ahead, bound for San Francisco skyscrapers. Crocheted sweaters followed, headed to visit retirees in the Berkeley and Oakland Hills. Prevailing easterly winds spared most of the Bay Area from the toxin; the hills trapped it over the rest of Oakland.

Lowlanders entered, all black people. Short-lived gentrification at the turn of the century and a recent return of hipsters, artists, and apostles of impending revolution notwithstanding, these neighborhoods had been predominantly black since the 1940s. Most residents couldn’t afford to leave their homes and had stayed. If they wore masks, most were fine, as it was primarily a respiratory toxin. Ocular and dermal lesions only afflicted those who routinely went out unprotected on high-toxin days.

The immunocompromised were more vulnerable, as were the elderly and the very young.

Daphne’s eyes darted between these new passengers and the continuing ones. What differences did she notice? The tightly curled hair? The dark-colored skin?

The festering sores on the cheeks, foreheads, and hands of those wearing shabbier clothing? The economic downturn had forced many Oaklanders onto the streets where they were exposed twenty-four seven. Joe tried not to stare. He tried not to cry.

It was his fault.