Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

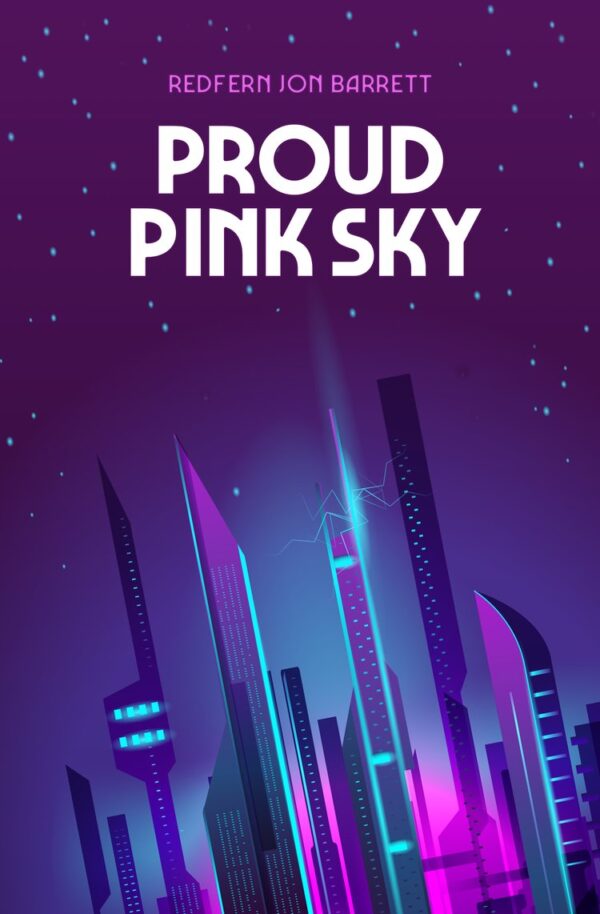

Today: Redfern Jon Barrett (they/them) is author to novels including Proud Pink Sky, a speculative story set in the world’s first LGBTQ+ state – which will be released by Bywater Books in March 2023. Redfern’s essays, reviews, and short stories have appeared in publications including The Sun Magazine, Guernica, Strange Horizons, Passages North, PinkNews, Booth, FFO, ParSec, Orca, and Nature Futures. They are nonbinary, have a Ph.D. in Literature, and currently live in Berlin. Read more at redjon.com.

Author Website https://www.redjon.com/

Author Mastodon @Redfern@mastodon.social

Thanks so much, Redfern, for joining me!

Welcome to my weekly Author Spotlight. I’ve asked a bunch of my author friends to answer a set of interview questions, and to share their latest work.

Today:

Thanks so much, Redfern Jon Barrett, for joining me!

J. Scott Coatsworth: When did you know you wanted to write, and when did you discover that you were good at it?

Redfern Jon Barrett: I discovered that I loved writing back in my twenties, when I was doing my PhD in Literature – I loved doing research, but academic writing is something very specific, and I started to long for something wild and uncontrolled. Even though I’ve always loved books, I’d always thought of writing fiction as something other people do. It was when I was visiting family during the holidays that I convinced myself to “Just try. Just this once.” I haven’t stopped since.

JSC: What do you do when you get writer’s block?

RJB: This might be an annoying answer, but I’ve actually never had writer’s block. I think it’s because I never, ever just sit down in front of a blank screen. The ideas have to come first, and I always have at least the start of what I’m going to write before my fingers hit the keyboard. If I don’t have any ideas then I go for a walk. A long walk, by myself, sometimes while listening to the same track on repeat. After a while the first sentence will form, and the rest will follow.

JSC: If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be?

RJB: Those books you love? The ones that are your comfort, your safety, your escape? You can write them too.

JSC: What are some day jobs that you have held? If any of them impacted your writing, share an example.

RJB: I’ve worked a lot of side jobs in my time, but probably the one that stuck with me the most was working in an elementary school here in Berlin. My task was the organize games and workshops for the kids to improve their English, and they loved me because I was the fun adult; you feel like a rock star when you arrive, with a crowd of kids running up to you shouting your name. I write queer fiction, but I make sure to represent, for example, young mothers and their kids, never forgetting the presence of children – and being sure not to loose touch with the curious, excited, child-like parts of myself when I write.

JSC: What is the most heartfelt thing a reader has said to you?

RJB: That my book made them feel like they aren’t alone. I cried when I read that.

JSC: What’s your writer cave like? Photos?

RJB: Extremely colourful! I live in Berlin, where the fashionable thing is always to dress in black and white, and to decorate in a minimalist style. My space is therefore extremely unfashionable, but it makes me very happy. Here’s a picture!

JSC: Are there underrepresented groups or ideas featured if your book? If so, discuss them.

RJB: Being set in the world’s first gay state, Proud Pink Sky is all marginalized people – and their relationships with other marginalized people. I spent 20 years working with different queer communities, and I was always astonished by the divisions that can exist between people who really should be working together – whether it’s gay people being biphobic, or lesbians denigrating trans people, or even trans people attacking other trans people for not being as trans as them. The novel dramatizes these very real conflicts and struggles.

JSC: What was the hardest part of writing this book?

RJB: Getting the balance right – it was important to me that Proud Pink Sky covers as many queer perspectives as possible, from young gay men, to trans outcasts. to nonbinary people, while always staying both critical and sympathetic. Proud Pink Sky is also a work of what I call ‘ambitopian’ fiction, showing the extremes of utopia and dystopia, presenting a society that represents both hope and serves as a warning. That’s another difficult balance.

JSC: What inspired you to write this particular story? What were the challenges in bringing it to life?

RJB: Being a huge fan of dystopian fiction, I’ve thought a lot about utopia and dystopia, and I was very keen to explore the middle ground between the two. What can we learn from a society with very real extremes of both good and evil? The world always gets both better and worse, constantly shifting in different directions, and I wanted to represent that dramatic, ambiguous change. This is my first ambitopian novel, and I hope to write more.

I’m also kind of fascinated by how complicated different forms of oppression can be – I came out at 18, and very early on I noticed how many people who are marginalized themselves punch down on those who have it even worse. Why is that, and where does this instinct come from? As always, I wanted to explore.

JSC: What are you working on now, and what’s coming out next? Tell us about it!

RJB: At the moment I’m working on the release for Proud Pink Sky, and at the same time I’ve been working on a series of stories which explore what would happen if we were able to reverse the aging process, following different characters who each become ‘ageless’. I’m having a lot of fun with it!

And now for Redfern’s latest book: Proud Pink Sky:

In this stunning work of speculative urban fiction, Redfern Jon Barrett breaks down the binary between utopia and dystopia—presenting an ambitopian vision of the world’s first gay state.

A glittering gay metropolis of 24 million people, Berlin is a bustling world of pride parades, polyamorous trysts, and even an official gay language. Its distant radio broadcasts are a lifeline for teenagers William and Gareth, who flee toward sanctuary. But is there a place for them in the deeply divided city?

Meanwhile, young mother Cissie loves Berlin’s towering high rises and chaotic multiculturalism, yet she’s never left her heterosexual district—not until she and her family are trapped in a queer riot. With her husband Howard plunging into religious paranoia, she discovers a walled-off slum of perpetual twilight, home to the city’s forbidden trans residents.

Challenging assumptions of sex and gender, Proud Pink Sky questions how much of ourselves we need to sacrifice in order to find identity and community.

Publisher | Amazon | | B&N | Book Depository

Excerpt

When she was a little girl, Cissie had read picture books all about handsome princes and beautiful princesses; books which were, without exception, the only literature allowed that wasn’t stamped with a golden cross. Once she’d learned these fairy stories by heart, Cissie’s parents had gifted her animated movies, and so she’d watched and re-watched Snow White and Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella until the videotapes were chewed into buzzing, fuzzing static.

There must be some way of becoming one of these princesses, so she reasoned. She’d perch herself in front of the television set for hours, her brow furrowed in single-minded concentration, and after months of studious analysis she’d arrived at three conclusions.

The first was, to her young mind, the most appealing. According to the movies, each princess would summon small animals to do her bidding. For years Cissie dreamed of this animal menticide, of commanding mice and bluebirds and becoming dictator to all woodland creatures. It seemed a rather more substantial prize than marriage to some willowy prince.

Cissie’s second conclusion was that she would need to be placed in mortal, supernatural danger. This prospect seemed quite exciting, particularly as her world—which comprised, almost exclusively, of the cozy farm-style house in which she was raised—seemed rather tame and limited by comparison. If there was danger, well, at least something was happening to you. Besides, were she to die she would simply reappear in the Heaven her parents so often talked about, and which surely was much bigger than their small Ohio home.

Her third conclusion had been the least agreeable. There was no avoiding the fact that these stories always ended with a marriage, which in turn was sealed with a chaste kiss. Cissie could do without these princes, yet it seemed there was no way of acquiring queenhood and the corresponding royal superpowers without one. So she approached the subject with an adult pragmatism, neither drawn to nor disgusted by these boyish regents. They were simply a means to an end.

These infant fantasies changed with adolescence. Ashamed of her blood-dotted underwear, she’d thrown all her clothes straight into the laundry hamper, and later that day her mother had sat upon her bed, patted the ancient quilt, and told Cissie to join her. With her thin face pulled tighter than Cissie had ever seen, she’d dished out opaque advice: You’re a woman now and This is our burden and It’s part of His plan for you and your husband. The shared prayer her mother led afterward lasted longer than the talk itself, and though Cissie still had no clue as to why she’d bled, she’d been left with the impression it was somehow because of men. It was surely a warning, her body cautioning her away from boys. Especially handsome princes.

Yet Cissie was an inventive child. Men were dangerous, that much was true, but perhaps women were safe. This led to the natural conclusion that she could avoid the terror of a prince by marrying a princess instead. So she’d invited her one friend, another homeschooled girl named Susan Michaels, up into the attic and into her old playhouse; which to grown-up eyes was an ancient refrigerator box with hand-cut holes for windows. With Susan safely inside, Cissie had sealed their relationship with a kiss.

Her friend’s next words had opened the door to another world. You’re a dyke, Susan had said, her little face stern with condemnation. She’d told Cissie that women who kissed women were dirty and sent to a special land far away. Susan knew so because her aunt had gone there, and once you left you never came back.

Of course Cissie had been surprised. The idea to marry another girl was all her own, and it had never occurred to her that someone else might have thought of it first. Questions had piled upon questions. Why could you never return from this land? Why had it never been mentioned in any of her stories? And most importantly: Where was this other world?

#

Cissie had never kissed another woman, but nearly twenty years later this mysterious city would become her home.

Oh, it hadn’t been her idea; her youthful curiosity had been fickle, and besides, what family woman would choose to live in homosexual Berlin? Yet Susan Michaels had been right about one thing: Cissie had never returned to Ohio.

#

At first she’d wandered the criss-cross streets, staggering around while gawping up at the crowded overhead transit lines, a foolhardiness which twice resulted in stolen purses. She’d only later learned said streets were part of Hetcarsey, one of the Berlin’s two straight districts. Though it wasn’t pretty—in fact most of the tenements had a raw, unfinished look about them—it was thrilling, and so different to the wide boulevards and gleaming art deco towers she’d seen in the postcards. With millions of residents, Hetcarsey was practically a city unto itself, and while Cissie had since learned to walk with thief-deterring speed, she still marvelled at the noise, at the dizzying array of lives above and around her.

After six years she’d even honed her life to a fine routine. Not because she was a particularly precise person, but because the boundaries of her day allowed her to carve a cranny for herself, a Cissie-shaped hole in a dizzying, sprawling, unknowable city. After taking the kids to school (they would have a proper education, not the rote Biblical learning she’d received) Cissie was left with nearly two whole luxurious hours to wander, to chart this territory, to wallow in chaotic multiculturalism.